A HIDDEN hero was honoured over the weekend at the Yan Yean Reserve’s Caretakers Cottage, where the Friends of Yan Yean delivered a heartfelt tribute.

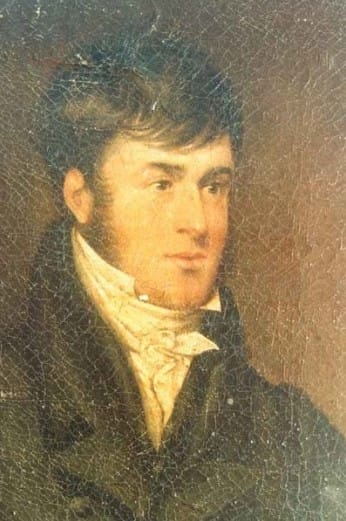

The afternoon was both nostalgic and educational, celebrating the remarkable achievements of James Blackburn. Melburnians owe much to his story, which began when he was sent as a convict to Tasmania. Through carefully prepared slides and narration, the presentation not only highlighted Blackburn’s contributions but also explored the history of how clean drinking water was stored and supplied to Melbourne’s rapidly growing population after colonisation.

Backtracking, Blackburn was born in 1803 and was schooled with his brothers in Upton Village, historically in Berkshire, England and surveying became his profession.

Married at the age of 23, to Rachel Hem, a year later he became employed as an inspector for the commissioners of sewers for the London districts of Holborn and Finsbury.

Ambitiously, he also turned his hand to property development, financing the project with his own money to make ends meet in between its property sales, he forged a cheque to the value of £600 (or $1200) using the names of his employers.

Blackburn was sentenced on May 20, 1833, to transportation for life despite the fact that the cheque was never cashed and his employees vouched for his reputation. Incidentally, the project was completed by another party and later, its mastermind was later praised for its genius, but Blackburn never received the acknowledgement.

Blackburn arrived at Hobart Town later that year in the Isabella; its fourth convict voyage, and notably along the way he supervised male children under ten who were onboard without an adult while Mrs Blackburn and their daughter also arrived safely in the Augustus Caesar two years later. Once their eldest son James finished his education, he joined the family seven years later.

Between 1804 and 1853 more than 70 thousand convicts were sent to Tasmania to work, certainly an unexpected population boom.

The couple raised another eight children together in between Blackburn serving his time designing roads and bridges for the responsible authorities who colonised Van Diemen’s Land as it was known, until he was given a pardon in 1841.

Twice, previously, in 1836 and 1839 applications for a pardon were refused.

To make ends meet, Blackburn sought private contract designs and some of those included what is now worldly architecture; the St Mark’s Church in Pontville and St Matthews Church in Glenorchy respectively to name a few.

Blackburn was not credited for any of those projects, the signatures instead were those of the public servants at the time, Irish born Roderic O’Connor and Scotsman, Alexander Cheyne.

IN time, the need for bold new infrastructure diminished but the family’s debts accumulated and it was thanks to his wife’s inheritance that they were able to clear their debts.

In 1847, Blackburn made his way by sea to Port Phillip Bay where Robert Hoddle, appointed by Governor Brisbane was surveying and developing a European colony and on April 16, 1849, the Blackburn family of 12, sailed in the Shamrock for Melbourne.

Immediately Blackburn set up practice as an engineer and architect.

Melbourne’s water supply, the Yarra River, was being used for industrial and domestic waste, and even worse human and animal waste.

Typhoid was rife, at the time it was known as colonial fever and there was exploitation as those who could, would cart clean water from upstream to sell downstream to those who could afford it.

Blackburn created the Water Authority; four citizens strong, they fitted tanks with charcoal for filters and sold it as a more affordable rate. He was back in business, doing what he was educated for and he rejoiced when he became officially employed as Melbourne’s City Planner in 1849.

Water purity worsened still, typhoid showed no signs of slowing down. Decisions needed to be made as to where to source fresh water from. Was it going to be Mount Macedon, Mount Disappointment, Darebin Creek, Plenty River, The Dandenongs Ranges or the Dights Falls near Abbotsford?

Yan Yean was Blackburn’s preference and he advocated for its development with a design that still delivers clean drinking water today. Three years later, in late 1853 the projects first sod was turned— the basic design and fundamental concept supplies Melbourne’s water to this day.

Typhoid took the lives of five of Blackburn’s children including his eldest daughter. They sadly died within a few days of each other driving Blackburn even harder to produce his greatest non-architectural work.

Despite his original vision, the plans were carried out, although somewhat modified, and with Blackburn in a subordinate position.

By June 1854, the Caretakers’ cottage was completed; four rooms with a separate kitchen perhaps it was designed by Blackburn himself.

Blackburn died of typhoid in February 1854, the colony had lost its greatest engineer and yet he is buried in a modest site in Parkville, Melbourne General Cemetery. He never got to see the reservoir completed.

English born Clement Hodgkinson who came to be a public servant in Victoria was one of the champions for the Yan Yean Reserve and later he pushed for the Blackburn Creek to be named in his colleague’s memory and perhaps indeed the suburb only 16km east of Melbourne.

Melbourne’s population reached 200,000 the day the reservoir was completed.

Between 1892 and 2012, more clean drinking water storages were mimicked by Blackburn’s technical proficiency, resourcefulness and fecundity of imagination as a designer.

Melbourne water facilitates the storage, filtration and delivery of reservoirs including Toorourrong or Jacks Creek Whittlesea, Sugarloaf, Maroondah, O’Shannassy, Silvan, Tarago, the Thomson, Upper Yarra, Cardinia, Greenvale and finally the Victorian Desalination Plant in Dalyston and Park Victoria manages its reserves.

James Blackburn junior went on to become an engineer.